Susan Oman gave her first keynote at Tate Liverpool last week. Below are some sections of the presentation and some thoughts on the plenary panel.

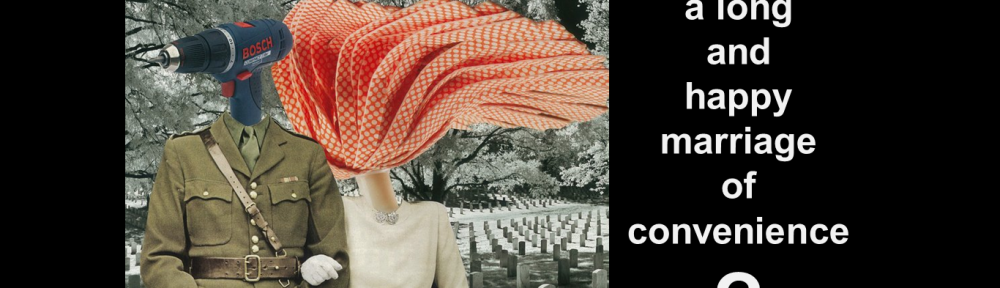

Culture is frequently described in terms of its relationship to well-being. Often, the implication being, that culture is only as GOOD as the quality of its attachment to well-being. Well-being is the patriarch, the most powerful and the one to do the serious work of policy, while culture is there to make us feel pretty. While playing with the ways in which the culture – well-being relationship is represented, the serious work of my provocation is to ask for a rethinking of this portrayal in order to move forward. To break not only the Temples of Culture, to cite the name of this event, but what seem to be sacred depictions of culture, as relative to well-being, in policy.

I was asked to give my first keynote on Friday – a provocation to inspire the plenary session for an Arts Health and Well-being Symposium at Tate Liverpool. The event, Breaking into the Temples of Culture: Exploring Arts, Health and Well-being Initiatives in the Community was organised by the Institute for Public Policy and Professional Practice, a cross-disciplinary research and knowledge exchange initiative.

I’ve copied the abstract below:

The UK government is one of many looking to decipher and track national well-being as an alternative measure of progress. The connection of cultural life to ‘progress’, and ‘cultural participation’ to individual, community and national well-being has been reasoned since Aristotle and Plato. More recently the UK’s ministry of culture invested £1.8million in an evidence programme that aimed to substantiate this and other associations to prove the value of culture. Yet despite the long theoretical history and recent financial investment in the ‘culture – well-being’ relationship, ‘culture’ was absent from the UK’s well-being measures for their first two years.

This presentation explores the assumed relationship between ‘culture’ and ‘well-being’ by tracking the two concepts through recent cultural policy. It presents particular ‘moments’ in recent history that highlight how the relationship is misunderstood and misrepresented. It will aim to demonstrate that this is indicative of wider problems regarding conceptions and articulations of participation in cultural policy, and well-being in wider policy at present.

The other speakers’ abstracts and bios can be found here.

Nick Ewbank of NEA, Folkestone and Adele Spiers, of SOLA ARTS, Liverpool accompanied me on the plenary panel. Adele’s first reflection was that culture was somehow always seen as positive, and that culture meant very different things to those who use SOLA ARTS, where she works as lead artist and art therapist. This led to a broader discussion on the ways in which culture is both personal and social and led Adele to question the necessity of labels on culture.

Problematising culture’s labels, and the assumptions about what well-being might mean in different cultural contexts, is key to the work I am doing – and to the broader UEP project, of course. That only some activities count as culture in governance terms presents imbalanced cultural policy that reproduces social inequalities. This is aggravated by some aspects of the well-being agenda, which coerce us to think that participating in particular activities is beneficial to well-being. We are pushed into a state where we are both trying to maximise our well-being and hoping to be deserving of well-being; and this is something I have found in my fieldwork time and time again.

The ways that well-being is used as a political tool to change people’s behaviours and practices can actually have a negative effect on how people feel about themselves. This was echoed by someone in the audience at the Tate, who questioned why she no longer felt that it was seen as OK that she didn’t feel great all the time. My findings show that this is increasingly the case; that people feel responsible for not demonstrating well-being in their day-to-day lives, and that they feel shame as a consequence. This is contrary to policy expectations, as the increasing awareness of mental health issues and the political importance of well-being should be reducing, rather than exasperating this problem.

Some of the best culture comes from being unhappy, suggested one respondent, and this moved into a discussion point on the importance of sub-cultural forms to well-being, with punk being at the forefront of the conversation. These cultural forms tend to subvert the norms of cultural representation (at least in their early days) and contend that you actually don’t have to appear like you are thriving all the time to others. Political voice and expression is prominent in much of the well-being literature, and so spaces where you are able to express that you are unhappy with the system, or reject dominant systems, is a key aspect of well-being that is often overlooked.

Nick picked up on how my presentation centred on an idea of well-being that had been institutionalised. He posited that well-being should be thought of as disruptive – in a good way. This has left me thinking about Dave Beer’s Punk Sociology, which uses a punk ethos to inspire sociology and to cultivate a vibrant future for the discipline. I wondered whether both cultural policy and well-being disciplines could benefit from such an approach in order to address their indulgent, self-congratulatory elements which are wrapped up in their own sense of self importance. I would argue these characteristics limit the capacity for change that these disciplines can effect in their current forms.

The institutionalisation of well-being and culture has led to a stereotypical idea of what their relationship is and can be. The conversations at Tate Liverpool last Friday showed that across the diversity of professions using a form of culture in some way to effect an idea of well-being, there are a broad range of practices and interpretations of cultural policy for social good. While this is not a wholly new conversation, the day highlighted – for me – the need to continue to converse across boundaries of place, discipline and practice, and to continue to work with and not against different approaches. Only then can we break down the temples of culture to think about what positive social change might be, and culture’s various roles in that.

Today, I propose that as with any stereotype of marriage, the culture-well-being relationship is often an unrealistic portrayal. That if culture is seen as the subservient spouse, then it often has greater responsibility to the relationship than assumed from the outside, much as the stereotypical wife of any powerful man. Conventional representations also tend to ignore how internal dynamics change as the relationship evolves over its life course, as it has to addresses problems and stressors outside the relationship. Well-being’s importance as a policy tool is based on how it is presented as an alternative measure of progress, and I am interested in well-being’s progression as a policy tool; and how, perhaps culture is less about mopping up behind well-being, and instead clearing the way for this to well-being’s advancement.