Last week saw a gathering of the AHRC Connected Communities (CC) clans on the outskirts of Edinburgh for their 2013 Summit. These annual meetings provide opportunities for projects funded under the CC programme (around 250 to date) to network and ‘show and tell’ their work. The three-day event included a day on early career research development, a programme networking day and, finally, a ‘Showcase’ aimed at a non-academic audience, which profiled a sample of the CC projects through exhibitions, posters, workshops and performances. The Showcase model was first trialed by the AHRC at an event in London in July, where it was a great success. Once again, a striking feature of this final day was the way in in which it illustrated just how creative academics can be.

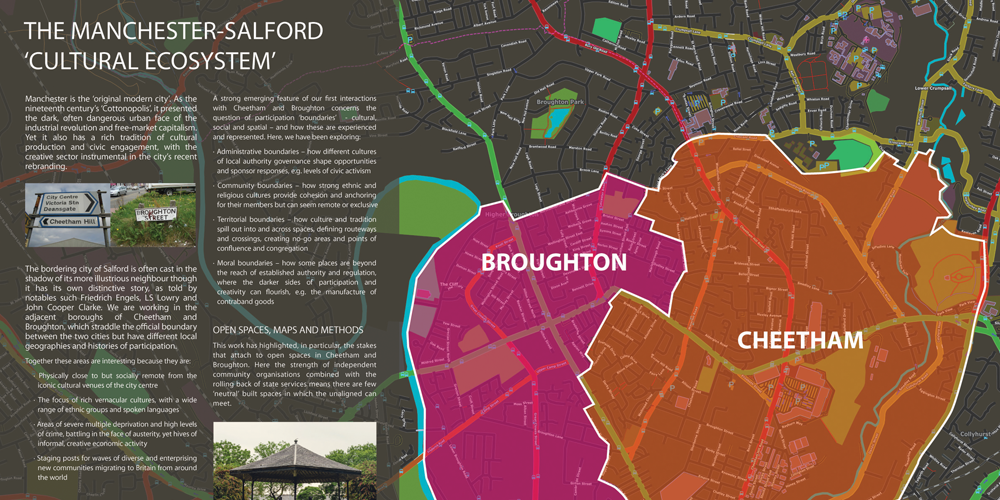

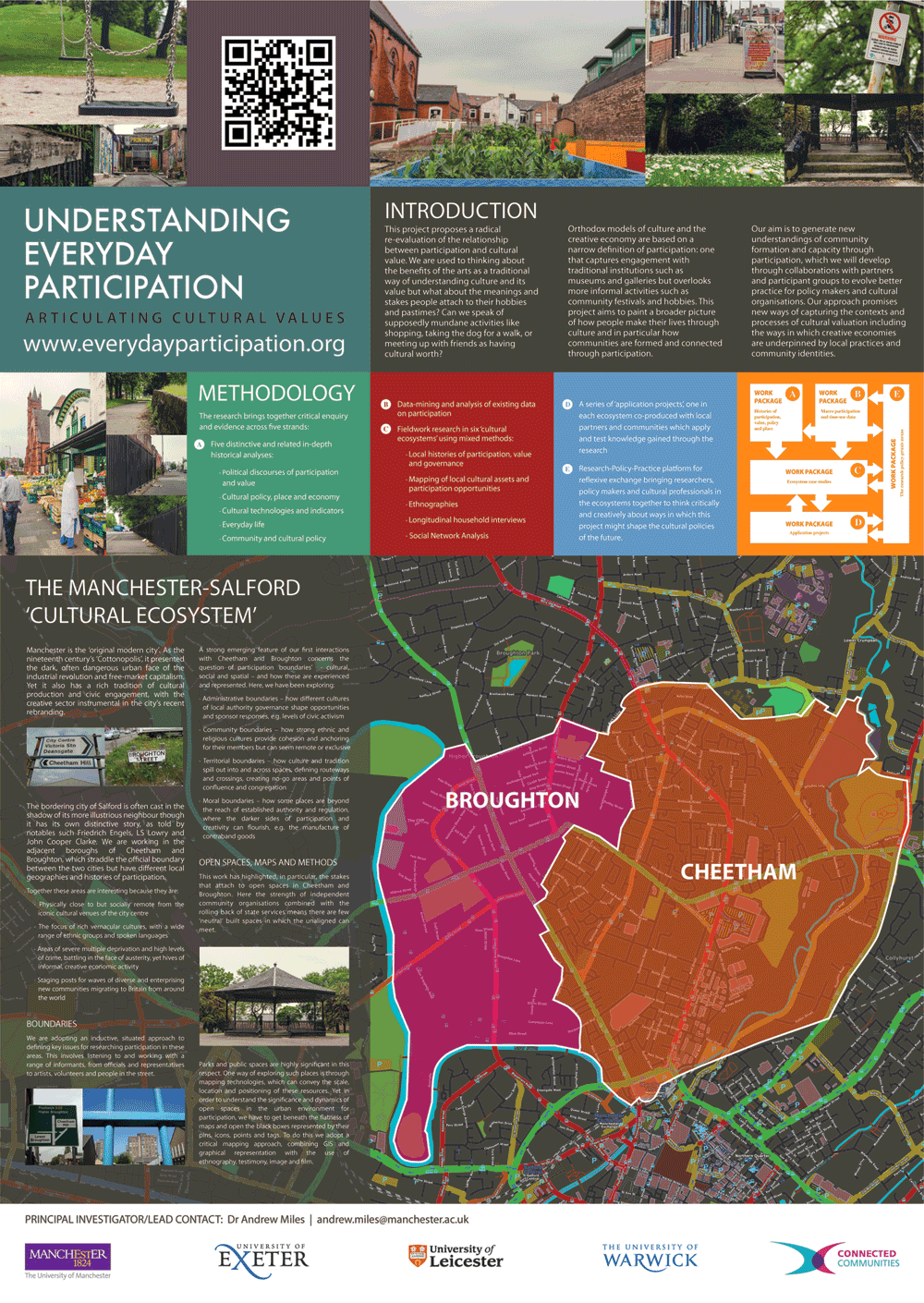

IMAGE: section of our poster for the connected communities summit. Full poster below.

Following on from previous summits, a central theme informing discussion concerned the issue of ‘co-production’ between academic researchers and the various publics they are working with. Specifically, attention focused on the balance of power within collaborations with calls for funding and management structures to be amended to allow community groups direct access to resources and to take the lead in driving projects. This is a debate that rehearses important questions about both research methods and the role (and responsibilities) of the academic researcher in society, which, incidentally, are also the subject of a forthcoming CC symposium in November.

For me, some of the conclusions that seemed to be emerging were slightly unsatisfactory. By way of an opening frame for discussion during the networking day, Mary Brydon-Miller gave a warm and engaging plenary presentation about action research. This highlighted how her work with and within communities troubles traditional models of academic expertise and Western dominance in the setting of the intellectual agenda. Not a lot to object to here but there is danger, I feel, when this tips over into a type of thinking that sees the process of community engagement as sovereign in terms of knowledge generation or co-production as the only way that academics can affect democratic research outcomes. In the first case, I would argue that there is an important place for theory in community-based research and that praxis isn’t its only source. Secondly, while co-production can clearly profile and enable community groups, claims about redistribution effects – at this scale and in the context of projects where community is prefigured and represented by intermediaries – appear somewhat symbolic. At the end of the second day, Leadership Fellow Keri Facer asked how CC could add up to more than the sum of its parts. One suggestion I would make, especially bearing in mind the programme’s positioning in relation to the ‘Big Society’ agenda, is that we might examine CC projects’ collective contribution to an understanding of structured inequalities and in particular how these are maintained culturally and might be addressed politically.

One medium of co-production that figured prominently at the Summit and which is an interest shared by the UEP project concerns ‘asset mapping’. In the context of unofficial or informal participation practices and the value that attaches to them, it is important to know where people locate resources, how these are distributed and organised spatially, and how the resulting configurations compare with official maps of cultural and leisure facilities. Two great initiatives on display at the Edinburgh Summit were the Creative Citizens and MapLocal projects. The former uses an interactive approach rooted in planning which employs a variety of props to explore and prioritise a community project’s assets, while the latter has developed a smartphone app which allows people to create content on the move and then mark and upload it on to a Google Map.

UEP’s contribution to the Edinburgh Showcase addressed the theme ‘Places of Everyday Participation’, around which we produced this poster and ran a workshop that was led by project research associates Delyth Edwards and Mark Taylor.

Scoping work with various constituencies in the neighbouring areas of Broughton in Salford and Cheetham Hill in Manchester, which are the focus of the first of UEP’s six empirical case studies, has revealed the importance of participation boundaries. These operate both between and within these areas and also in their marking off from the iconic cultural terrain of Manchester city centre, just a 20-minute walk away at the bottom of Cheetham Hill Road. Both areas are characterised by strong but in many ways mutually exclusive communities, defined by different ethnicities, religions and languages groups, and this places a premium on open and public spaces as neutral meeting places.

During the breakout session, Mark described the work he’d been doing using Google Earth together with local authority and commercial sources to map established assets while adding layers, tags and images to compare and contextualise these with the resources and issues identified by focus group informants. Delyth read from her walking ethnography about moving through different types of boundaries – physical, cultural, regulatory, historical – in Broughton and Cheetham, and in the process happening upon both present and past places of participation. In between, Elaine Speight from local project partners Buddleia – a commissioning agency for art and public space – spoke about their work with residents in reclaiming and transforming open spaces. The session ended with workshop participants exploring the use of iPads as interactive mapping tools.

UEP is using asset mapping as a core methodology across all of its six case studies. As we develop our work in this context, it is clear to me that there is much to be gained by learning from and sharing with the mapping projects elsewhere in the CC programme. Alongside this, one of the key aspects of UEP’s approach to mapping is to interrogate the method itself, which it is doing by placing it within a mixed methods framework that opens up a number of lenses on the spatialisation of knowledge about participation. In the spirit of ‘critical mapping’ (Crampton 2010), we are asking ‘what do maps do’ to help construct participation and participants. In an evaluation of ‘participatory mapping’ (Elwood 2006), we are using ethnography to get beneath the flatness of maps and to unpack the black boxes represented by their icons, pins and tags; in-depth interviews to mobilise and redraw them with participation narratives; and social network analysis to probe the relational dynamics that frame spaces as places of participation.

Andrew Miles 11.07.13